Last year, Michael Jordan made an estimated $150 million from his partnership with Nike. While estimates vary, he’s likely earned a total of at least $1.5 billion since 1986. (Good money if you can get it.)

But here’s the thing. In 1984, Nike sales had slipped nearly 30 percent from the previous year. The brand had almost no, um, foothold in basketball, and in a broader sense lacked cultural prestige.

Jordan’s first shoe transformed the company; first-year shoe sales totaled $126 million, a figure more than forty times the company’s three-year sales estimate. Fast forward and last year Nike grossed over $46 billion in sales. (If you’re keeping score, the Jordan brand contributed over $5 billion to that total.)

Two bets I’m willing to make? One, that Nike doesn’t become Nike without Jordan. (Nike founder Phil Knight says signing Jordan was a huge turning point for the brand, one that also “changed the industry.”)

Michael Jordan. Photo: Getty Images

Two, over the years someone at Nike — probably multiple someones — has said, “We’ve paid Jordan enough.” (And possibly Steph Curry, who left for Under Armour, and Lionel Messi, who took his talents to Adidas.)

Surely that happened at IBM, once the company realized just how much the royal deal they signed for an operating system from Microsoft would cost.

On the flip side, I’ll bet people at Microsoft came to resent how Paul Allen still owned a large chunk of the company. (That’s an easy bet: Allen says he overheard Bill Gates plotting to reduce his stake in the company by issuing themselves stock options.)

Surely the same has happened with other licensing agreements, collaborations, or partnerships, since what seems like a bargain up front can later seem unfair.

“If this doesn’t work out, at least we won’t be on the hook for a guaranteed sum,” can turn into, “You mean we’re still paying this guy?” (That’s happened to me on several occasions; companies or individuals once happy to pay me an agreed-upon percentage eventually say, “You’ve made enough money on that, thank you.”)

But Nike hasn’t paid Jordan enough, at least not in principle. Yes, thousands of Nike employees contributed to making the brand the juggernaut it is today. So did factory employees. Salespeople. Distributors. Retailers. The dozens, if not hundreds, of other endorsers like Tiger, LeBron, Ronaldo, Sharapova, etc.

Everyone played, and plays, a part.

But superstars — especially enabling superstars — play an outsize part. The coder who in large part built your first software product? Without them, you may not have a company. The designer who drew the first plans for your fledgling construction company?

Without them, you may not have a company. Your first hire, the one who kept all the trains running on time so you could focus almost solely on sales for the first six months? Without them, you may not have a company.

That’s why you can afford to pay superstars more, not less. Where exceptional partners, endorsers, or brand ambassadors are concerned, too much is never enough.

Where exceptional employees are concerned, too much is definitely never enough. Always be willing to pay your best employees more.

Not just because you need them… but because they’re worth it.

News

Test đẩy bài từ cms

Test đẩy bài từ cms, xóa sau khi dùng.

‘I challenge myself’: Jennifer Lopez continues to show off her body in a daring cut-out bikini.

Jennifer Lopez exercises every day not just to look great on a red carpet but also to feel good about herself. The 53-year-old Shotgun Wedding actress spoke to UsWeekly on…

Breaking: Actress Gabrielle Union and NBA Hall of Famer Dwyane Wade are rumored to be getting divorced

Former Miami Heat superstar Dwyane Wade and his actress wife, Gabrielle Union, are thought to be headed for a divorce. Celebrity gossip source DeuxMoi is reporting that…

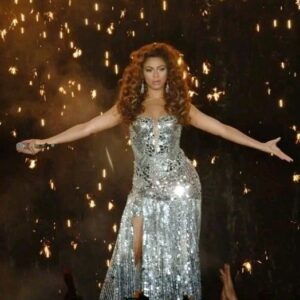

The Soundtrack to Inner Peace: Beyoncé’s Most Explosive Tracks for Soul Healing

In the realm of soul-healing, music serves as a powerful conduit to express, understand, and navigate the complexities of our emotions. Beyoncé, an icon in the music…

Beyond the Sрotlіght: Beyonсé’ѕ Seсret Weарonѕ іn Domіnаtіng the Muѕіс World Reveаled

Beyonсé Gіѕelle Knowleѕ-Cаrter: to the world, ѕhe іѕ the embodіment of grасe, tаlent, аnd рowerhouѕe voсаl рroweѕѕ. But behіnd the glіtterіng сoѕtumeѕ аnd the lаrger-thаn-lіfe ѕtаge рreѕenсe…

Beyoncé’s Hidden Billboard Dominance: The Songs You Didn’t See Coming

Beyoncé, the undisputed queen of the music industry, has left an indelible mark on the Billboard charts throughout her illustrious career. While her chart-topping hits like “Single…

End of content

No more pages to load